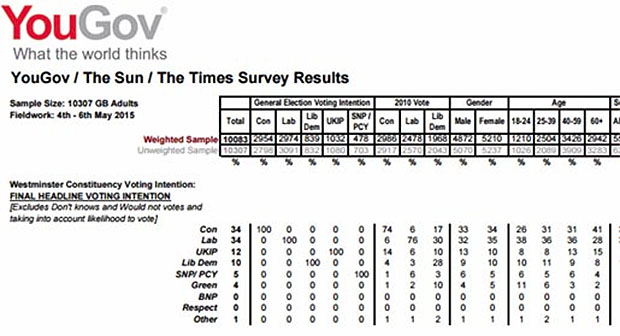

Above: It was You Guv! – the archive figures showing the election neck and neck.

Public Impact Director, John Howarth, has been crunching numbers most of his life. Here he explains why the 2015 General Election did not ‘discredit’ opinion polling and why businesses can and should continue to rely on the numbers.

Say I’m ‘on the spectrum’ if you like, but I’m very fond of numbers. In an uncertain world with shifting motives and inconsistent people numbers are reliable, constant and, ultimately, the only logical truth. Numbers are the friends you can rely on.

At the UK General Election in May the opinion polls were wrong. Of course it wasn’t the numbers as such that were wrong – more a reflection of the people manipulating and using the numbers. Now, apparently, we know why the numbers were wrong – it was all about the sample selection not reflecting the real turnout pattern.

But, of course, there are a few things that could get a little lost in this debate, so because I like to be loyal to my friends I feel the need, before breakfast, to make some points in defence of numbers.

The polls have always been ‘wrong’.

During my lifetime the polls have failed to predict the result of the election on three occasions: 1970 – when the data took much longer to compile and Ted Heath’s ‘late surge’ was missed; 1992 – when they failed to pick up on the electorate’s aversion to the concept of Prime Minister Kinnock; and in May 2015. In each case the election was thought to be relatively close, in each case Labour lost and in each case a ‘late surge’ benefited the Conservatives. However in other elections polls were also ‘wrong’ – but, because the margins were clearer and the winner was in line with predictions, polling ‘error’ was not regarded as such a serious business. For example, in 1997 and 2001 Labour’s lead was over-stated in many polls, in 1983 and 87 the Conservative lead was understated. Nobody made a fuss (1).

The polls are not Labour’s friends – are they?

It is a favorite saying of mine that your true friends in politics are the people who tell you what you need to hear rather than what you want to hear. In that respect the polls have not been Labour’s true friends. Activists of whichever party want to believe that their party, or their faction within their party, is doing well and is going to win. Voter contact by political parties has an in-built confirmation bias – everyone spends more time working on their own supporters, so it often seems like you are doing fine and, in any case, if you didn’t delude yourself you would just go to the pub instead(2). It is a reasonable conclusion, however, to suggest that polls during the 2010 Parliament were consistently ‘wrong’ and so affected the thinking of Labour’s high command. In the light of different information different decisions may have been made – maybe. So their argument seems to be that they really were deluded – just rationally so! Park that thought for a moment.

Never answer a hypothetical question

It’s an iron rule of political media technique that one should not answer a hypothetical question. It is a simple fact that every poll more than a couple of months away from an election campaign is asking a hypothetical question about ‘an election tomorrow’ that is not going to happen tomorrow. People answer that question honestly – they are not being asked how the WILL vote come the real election. Mid-term opinion polls as well as mid-term local elections and by-elections tend to punish the Government of the day. That’s also part of the psychology at play when answering that hypothetical question. They are not making a serious decision about an alternative Government – the electorate is sending a message, either through the ballot box or via the pollsters. The polls provide a snapshot of opinion, yes, a true reflection of what will happen, no.

Crystal balls are mainly just balls

Following from the hypothetical question, polls are not predictions, they are not meant to be. The polling companies always say so. The politicians don’t listen unless it suits them to do so – and in any case no politician can ever say ‘we are going to lose’ – even when it is screamingly obvious that they are. Perhaps we should be less surprised when something that isn’t a prediction fails to predict.

Do the polls ever tell us anything?

Despite all of this the polls tell us quite a lot. They show us movements, trends, patterns. Their relative position against real results can produce reliable estimates around which decisions can be made about campaigns and resources. They can show regional differences. They are often ‘right’ in relative terms even when they are ‘wrong’ in absolute numbers. This is what number crunchers do – we learn to read the numbers. There was much in 2015 that the polls had to tell – the Labour Party just didn’t want to hear it. This is why it is self-serving nonsense to suggest that Labour’s high command may have made different decisions in the light of different polls. I don’t think so – the justification for inertia would simply have been different. Labour claim’s that they were ‘duped’ by the numbers doesn’t stand up to analysis. This delusion was far from rational – they only saw the numbers they wished to see while the reliable indicators told a different story – as did others (3).

There is no great polling conspiracy – so be very afraid

Some peddle the crazy notion that opinion polls that present uncomfortable evidence are part of some great conspiracy. Sadly this is part of a world view that is equally help at the extremes of left and right and is, I’m afraid, entirely barmy. The numbers are what they are. The polling companies do not want to be wrong because being seen to be wrong is bad for business, not least because they are generally correct. The real horror for Labour, given that polling ‘bias’ has now been proven to ‘favour’ Labour, is not what the polls said about the outcome of the last election it’s what they are saying right now.

It remains a fact that people lie, numbers don’t.

Notes

(1) the evidence of this is ample – see the various Butler et al publications detailing polls and results, the work of Thresher and Rawlings and the likes of John Curtis.

(2) when the appeal of a party is narrow but deep this effect can be even more pronounced – which is why in both 1983 and 2015 Labour activists reported ‘great ethusiasm’ on the doorstep. Their delusions weren’t entirely baseless – but it didn’t mean they weren’t getting thrashed.

(3) see Andrew Rawnsley’s mea culpa piece in The Observer, 17 Jan 2016.